Facts from ECB CH4: Protein Structure and Function

| 1486 words- The Shape and Structure of Proteins

- How Proteins Work

- How Proteins are Controlled

- How Proteins are Studied

Note: one of the main things I understood better from reading this chapter is how much faster smaller things are than big things. Water molecules at room temperature are moving at roughtly 590 m/s. Enzymes are catalyzing roughly 1000 reactions a second. A cell uses millions of ATP per second.

The Shape and Structure of Proteins

- Proteins are made from long chains of animo acids held together by peptide bonds.

- The shape of the folded chains is constrained by noncovalent interactions between the side chains. For instance, nonpolar side chains tend to cluster in the interior of the protein.

- Proteins approximately fold in the way that locally decreases free energy. When the desired configuration doesn’t have a pathway locally leading to it unassested, chaperone proteins can help the protein along a more energetically favorable pathway. If the desired pathway will get disrupted without protection, chaperone proteins can form isolation chambers so the protein can fold in peace.

- The vast majority of proteins are between 50 and 2k amino acids long

- α helix and the β sheet are fommon folding patterns.

- Helixes are common because if you stack things on top of each other, then you’ll get some sort of helix, unless the things are stacked perfectly.

- Sometimes, misfolded proteins can cause other proteins to also misfold, creating self-perpetuating structures that result in disease.

- Proteins are organized at the level amino acids, how those amino acids form local structures, how those local structures cohere into an entire protein, and how proteins (sometimes) interact to form larger complexes.

- Proteins can have independent, compact and stable structures. For example, the bacterial catabolite activator protein (CAP), has a domain that binds to DNA and a domain that binds to cyclic AMP. When it binds to cyclic AMP, the protein changes shape, making the first domain able to bind to DNA, which promotes expression of a gene.

- Large proteins contain many domains, often connected by short, unstructured lengths of polypeptide chain, called intrinsically disordered sequences. About 1/3rd of all eukaryotic proteins also possess unstructured regions greater than 30 amino acids in length.

- Sets of proteins often share similarities in amino acid sequence and 3d conformation, suggesting they evolved from some common ancestor protein with a useful shape. For example, the serine proteases are a family of protein cleaving enzymes that are present in digestion and blood clotting, among other processes.

- Regions on a protein that interact with other molecules are called “binding sites”. These can recognize other proteins, allowing for larger proteins with quaternary structure. The simplest case: two copies of the same protein can form a symmetric complex with itself, e.g. hemoglobin contains 2 identical α-globin proteins and two identical β-globin proteins.

- Chains of identical protein molecules can be formed if the proteins bind to each other in an identical way. For example, an actin filament is a long helical structure formed from many molecules of the protein actin

- Extracellular proteins are often stabilized by covalent cross-linkages. The most common covalent cross-links in proteins are sulfer-sulfer bonds (disulfied bonds), which are formed by an enzyme in the endoplasmic reticulum.

How Proteins Work

- Proteins fundamentally work by binding to other molecules. Any substance bound by a protein is referred to as a ligand for that protein. Strong bonds between ligand and protein are only possible if the shape of the ligand matches the shape of the protein very well, since the binding forces are weak interactions

-

Humans produce billions of different antibodies, each with a different binding site. Antibodies are Y-shaped with two identical antigetn-binding sites formed from several loops of polypeptide chain. Their amino sequence can vary without altering basic structure, meaning large number of binding sites can be generated by changing only the length and amino sequence.

- You can couple antigens to dyes and use them as molecular tags.

- Enzymes typically catalyze ~1000 reactions per second, with ranges from 1 - 100k.

- Lysozyme catalyzes a hydrolysis reaction between a single bond between two adjacent sugar groups in the polysaccharide chain, which breaks the bond in the cell wall of bacteria. Because the bacteria is under osmotic pressure, it then bursts.

- Many drugs work by inhibiting enzymes, i.e. binding to their binding sites and not letting go. Cholestral-lowering statins inhibit HMG-CoA reductase, which is involved in making cholestral in the liver

- Proteins often employ small, nonprotein molecules to perform functions that would be difficult or impossible using amino acids alone. For example, rhodopsin, the light-sensitive protein made by the rod cells in retinas, detects light using a small molecule called retinal. Retinal changes shape when a photo hits it, which is amplified by the protein to trigger a cascade of reactions that results in neurons firing.

How Proteins are Controlled

- The regulation of cells internal state is, in large part, a regulation of which enzymes are “on” or “off”. This occurs at many levels: the presence/absence of the protein can be controlled at the gene level or the speed of protein degradation. Protein-substrate interaction can be controlled by physical confinement, e.g. organelles. Finally, the proteins individual activity can be adjusted through more complex means, often built-into the protein.

- Enzymes sometimes have regulatory sites where non-substrate molecules bind to these sites and alter the rate at which the enzymes converts substrate to product.

- Molecules produced later on in a chain or reactions can inhibiti the production of molecules earlier in the chain, forming a feedback inhibition mechanism.

- Interactions between sites on molecules depends on a conformational change in the protein. If a protein has two binding sites, the binding of one of the sites causes the protein to change shape, which alters the second binding site. For feedback inhibition, the binding of the regulatory site causes the protein to spend more time in a shape where its active site is not so good at capturing the substrate.

- An enzyme that catalyzes the oxidation of sugar molecules spends more time in the “sugar oxidization” conformation in the presence of ADP. If there’s lots of ADP, the cell probably needs more ATP, so sugars need to be oxidized.

- Eukaryotic cells regulate protein activity by attaching a phosphate group covalently to one of the protein’s amino acid side chains. Since the phosphate group has two negative changes, this introduces a distortion in the shape. 1/3rd of the proteins in a typical mammalian cell are phosphorylated at any time.

- Cells contain hundreds of different protein kinases, each responsible for phosphorylating a different protein.

- Phosphorylation can take place in a continuous cycle, in which a phosphate group is rapidly added and removed from a side chain. This allows proteins to switch between states

- There are more than 100 types of covalent modifications that can occur in each cell, each playing its own role in regulating protein function.

- Proteins can also be modified on more than 1 side chain. Protein p53, which plays a central part in controlling how a cell responds to DNA damage, can be modified at 20 sites.

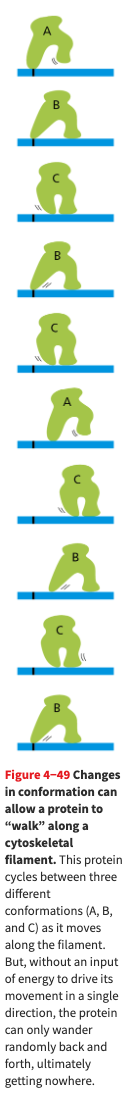

- A protein that is required to walk can move by undergoing a series of changes, but the changes will be reversible. In order to drive them in a single direction, one of the steps must be made unidirectional. The irreversibility is achieved by coupling one of the changes to hydrolysis of an ATP molecule

- Here is a cute diagram of a protein that cannot walk because it is not using any energy.

- Here is a cute diagram of a protein that cannot walk because it is not using any energy.

- The muscle motor protein myosin walks along actin filaments at about 6 μm/sec during muscle contraction.

- Many protein complexes are brougth together by scaffold proteins. These are large molecules that contain binding sites recognized by multiple proteins.

How Proteins are Studied

- Proteins can be purified by breaking cells, seperating out class that contains protein of interest, and doing series of chromatography steps.

- Electrophersis involves loading proteins into a gel and subjecting them to an electric field. This will cause proteins to move at different rates based on charge, mass, shape, separting them into bands.

- Proteins are identified with mass spectrometry by determining the mass of every peptide fragment, then consulted a database. This is sort of like a hash function you can apply to proteins, so you only have identify proteins the hard way once.

- X-ray crystallography can determine the 3D structure of proteins, however they must first be coaxed into forming regular arrays of proteins in the same orientation. This can take years of trial and error.

- Bacteria, yeast and cultured mammalian cells are used to mass produce insulin, human growth hormone, and fertility-enhancing drugs. Fertitlity enhancing drugs used to be made by vast amounts of the urine of postmenopausal nuns.

- Currently, millions of proteins have been sequenced, with a doubling time of around 2 years. The vast majority of proteins seem to belong to about 10k-20k structural domains.