Agents Over Cartesian World Models

| 8610 words- Abstract

- Introduction

- Consequential Agents

- Structural Agents

- Conditional Agents

- Problems

- Appendix

Coauthored with Evan Hubinger

Crossposted from the AI Alignment Forum. May contain more technical jargon than usual.

Thanks to Adam Shimi, Alex Turner, Noa Nabeshima, Neel Nanda, Sydney Von Arx, Jack Ryan, and Sidney Hough for helpful discussion and comments.

Abstract

We analyze agents by supposing a Cartesian boundary between agent and environment. We extend partially-observable Markov decision processes (POMDPs) into Cartesian world models (CWMs) to describe how these agents might reason. Given a CWM, we distinguish between consequential components, which depend on the consequences of the agent’s action, and structural components, which depend on the agent’s structure. We describe agents that reason consequentially, structurally, and conditionally, comparing safety properties between them. We conclude by presenting several problems with our framework.

Introduction

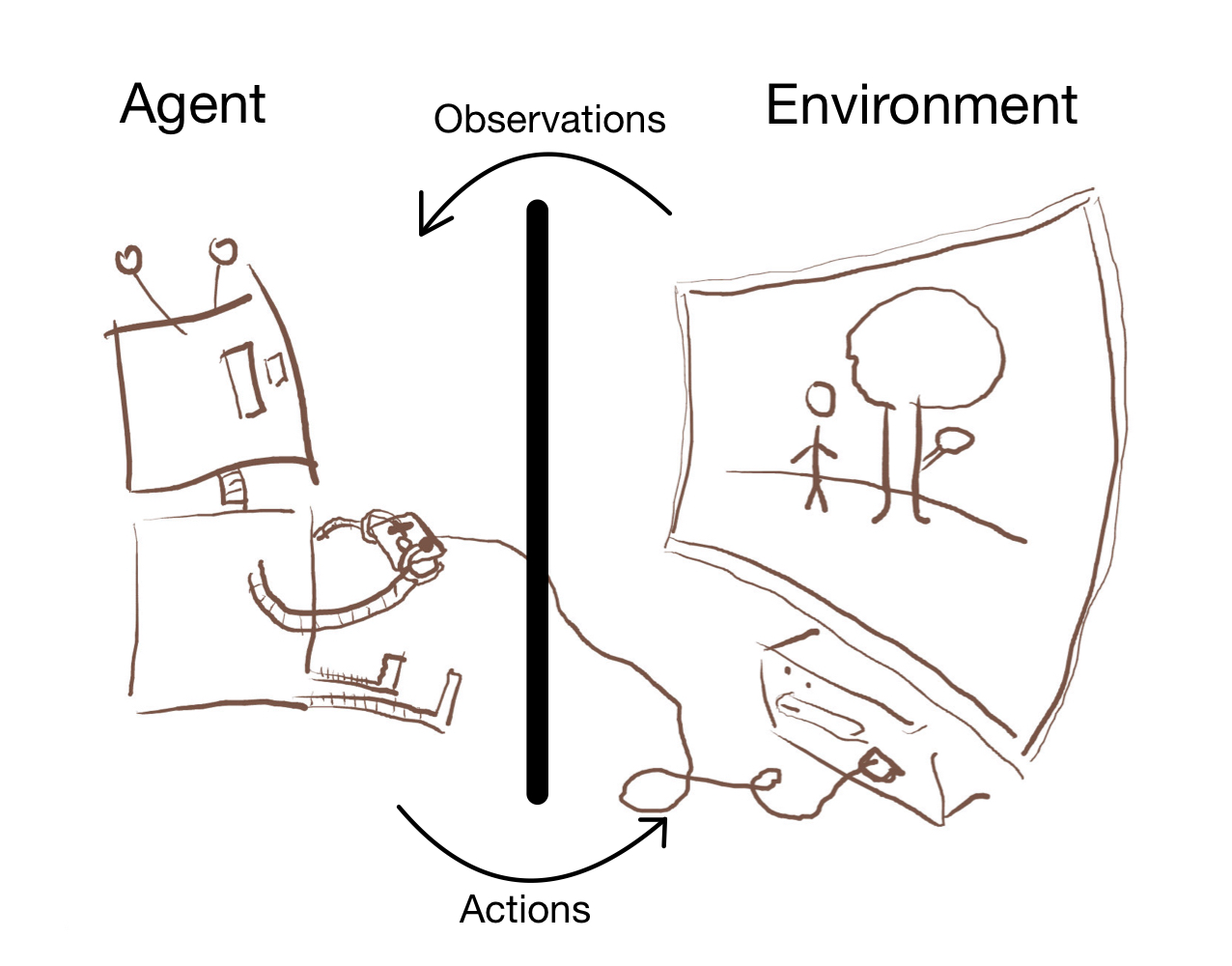

Suppose a Cartesian boundary between agent and environment:1

There are four types: actions, observations, environmental states, and internal states. Actions and observations go from agent to environment and vice-versa. Environmental states are on the environment side, and internal states are on the agent side. Let \(A, O, E, I\) refer to actions, observations, environmental states, and internal states.

We describe how the agent interfaces with the environment with four maps: \(\text{observe}\), \(\text{orient}\), \(\text{decide}\), and \(\text{execute}\).2

- \(\text{observe}: E \to \Delta O\) describes how the agent observes the environment, e.g., if the agent sees with a video camera, \(\text{observe}\) describes what the video camera would see given various environmental states. If the agent can see the entire environment, the image of \(\text{observe}\) is distinct point distributions. In contrast, humans can see the same observation for different environmental states.

- \(\text{orient}: O \times I \to \Delta I\) describes how the agent interprets the observation, e.g., the agent’s internal state might be memories of high-level concepts derived from raw data. If there is no historical dependence, \(\text{orient}\) depends only on the observation. In contrast, humans map multiple observations onto the same internal state.

- \(\text{decide}: I \to \Delta A\) describes how the agent acts in a given state, e.g., the agent might maximize a utility function over a world model. In simple devices like thermostats, \(\text{decide}\) maps each internal state to one of a small number of actions. In contrast, humans have larger action sets.

- \(\text{execute}: E \times A \to \Delta E\) describes how actions affect the environment, e.g., code that turns button presses into game actions. If the agent has absolute control over the environment, for all \(e \in E\), the image of \(\text{execute}(e, \cdot)\) is all point distributions over \(E\). In contrast, humans do not have full control over their environments.

We analyze agents from a mechanistic perspective by supposing they are maximizing an explicit utility function, in contrast with a behavioral description of how they act. We expect many training procedures to produce mesa-optimizers that use explicit goal-directed search, making this assumption productive.3

Consequential Types

We use four types of objects (actions, observations, environmental states, and internal states) and four maps between them (\(\text{observe}\), \(\text{orient}\), \(\text{decide}\), and \(\text{execute}\)) to construct a world model. The maps are functions, but functions are also types. We will refer to the original four types as consequential types and the four maps as structural types.

We can broadly distinguish between four type signatures of utility functions over consequential types, producing four types of consequential agents.4

- Environment-based consequential agents assign utility to environmental states. Most traditional agents are of this type. Examples include the Stamp Collector, a paperclip maximizer, and some humans, e.g., utilitarians that do not value themselves.

- Internal-based consequential agents assign utility to different internal states. Very few “natural” agents are of this type. Examples include meditation bot, which cares only about inner peace, happiness bot, which cares only about being happy, and some humans, e.g., those that only value their pleasure.

- Observation-based consequential agents assign utility to different observations. Many toy agents have bijective \(\text{observe}\) functions and could be either observation-based or environment-based. Examples include virtual reality bot, which wants to build itself a perfect VR environment, video game agents that value the observation of the score, and some humans, e.g., those that would enter the experience machine.

- Action-based consequential agents assign utility to different actions. Very few “natural” agents are of this type. Examples include twitch bot, which just wants to twitch, ditto bot, which wants to do whatever it did previously, and some types of humans, e.g., deontologists.5

Some agents have utility functions with multiple types, e.g., utilitarian humans with deontological side constraints are environment/act-based consequential agents. Some humans value environmental states and personal happiness, making them environment/internal-based consequential agents. Question answering agents value different answers for different questions, making them internal/act-based consequential agents.

Agents could also have utility functions over structural types. We defer discussion of such structural agents until after we have analyzed consequential agents.

Consequential Agents

Cartesian world models

We modify discrete-time partially observable Markov decision processes (POMDPs) by removing the reward function and discount rate and adding internal states. Following Hadfield-Menell et al., who call a Markov decision process (MDP) without reward a world model, we will refer to a discrete-time POMDP without reward (POMDP\R) and with internal states as a Cartesian world model (CWM).6

Formally, a Cartesian world model is an 7-tuple \((E, O, I, A, \text{observe}, \text{orient}, \text{execute})\), where

- \(E\) is the set of environmental states (called “states” in POMDP\Rs),

- \(O\) is the set of observations the agent could see (also called “observations” in POMDP\Rs),

- \(I\) is the set of internal states the agent could have (not present in POMDP\Rs),

- \(A\) is the set of actions available to the agent (also called actions in POMDP\Rs),

- \(\text{observe}: E \times A \to \Delta O\) is a function describing observation probabilities given environmental states (called “conditional observation probabilities” in POMDP\Rs),

- \(\text{orient}: O \times I \to \Delta I\) is a function describing internal state probabilities given observations (not present in POMDP\Rs),

- \(\text{execute}: E \times A \to \Delta E\) is a function describing transition probabilities between different states of the environment given different actions (called “conditional transition probabilities” in POMDP\Rs),

At each time period, the environmental state is in some \(e \in E\), and the agent’s internal state is some \(i \in I\). The agent \(\text{decide}\)s upon an action \(a \in A\), which causes the environment to transition to state \(e'\) sampled from \(\text{execute}(e, a)\). The agent then receives an observation \(o \in O\) sampled from \(\text{observe}(e', a)\), causing the agent to transition to internal state \(i'\) sampled from \(\text{orient}(o, i)\).

This produces the initial 4-tuple of context \(c_0 := (e, i, a, o)\) representing the initial environment’s state, the agent’s initial internal state, the agent’s initial action, and the agent’s initial observation. Subsequent time steps \(t\) produces additional 4-tuples of context \(c_t\).

MDPs are traditionally used to model decision-making situations; agents trained to achieve high reward on individual MDPs implement policies that make “good” decisions. In contrast, we intend CWMs to capture how agents might model themselves and how they interact with the world.

Consequential Decision Making

Agents making decisions over CWMs attempt to maximize some utility function. To emphasize that agents can have utility functions of different types, we make the type explicit in our notation. For example, a traditional agent in a POMDP will be maximizing expected utility over an environment-based utility function, which we will denote \(U_{\{E\}}(e, t)\), with the second parameter making explicit the time-dependence of the utility function.

More formally, let \(\mathbb T\) be the set of possible consequential type signatures, equal to \(\mathcal P(\{E, O, I, A\})\). For some \(T \in \mathbb T\), let \(U_T: T \times \mathbb N \to \mathbb R\) be the agent’s utility function, where \(T\) can vary between agents. Recall that \(c_t := (e, i, a, o)\) is at the 4-tuple of CWM context at time \(t\). Let \(c_t\vert_T\) be \(c_t\) restricted to only contain elements of types in \(T\). A consequential agent maximizes expected future utility, which is equal to \(\mathbb E [ \sum_{t = 0}^\infty U_T(c_t\vert_T, t)]\).

\(U_T\)’s time-dependence determines how much the agent favors immediate reward over distant reward. When \(t > 0 \implies U_T(c_t\vert_T, t) = 0\) the agent is time-limited myopic; it takes actions that yield the largest immediate increase in expected utility. When \(U_T(c_t\vert_T, t) \approx U_T(c_t\vert_T, t + 1)\) the agent is far-sighted; it maximizes the expected sum of all future utility.

Examples

Example: Paperclip maximizer

Consider a paperclip maximizer that can only interface with the world through a computer. Define a Cartesian world model \((E, O, I, A, \text{observe}, \text{orient}, \text{execute})\) as follows:

- \(E\) is all ways the universe could be,

- \(O\) is all values a 1080 x 1920 monitor can take,

- \(I\) is the set of internal states, which we leave unspecified,

- \(A\) is the set of keycodes plus actions for mouse usage,

- \(\text{observe}\) maps the environment to the computer screen; this will sometimes be correlated with the rest of the environment, e.g., through the news,

- \(\text{orient}\) maps the computer screen to an internal state, which we leave unspecified,

- \(\text{execute}\) describes how keycodes and mouse actions interact with the computer.

Additionally, let our agent’s utility function be \(U_{\{E\}}(e, t) = \text{the number of paperclips in\)e\(}\).

Many of these functions are not feasible to compute. In practice, the agent would be approximating these functions using abstractions, similar to the way humans can determine the consequences of their actions. This formalism makes clear that paperclip maximizers have environment-based utility functions.

Example: twitch-bot

Twitch-bot is a time-limited myopic action-based consequential agent that cares only about twitching. Twitch-bot has no sensors and is stateless. We can represent twitch-bot in a CWM+U as follows:

- \(E\) is all ways the universe could be,

- \(O = \{\emptyset\}\); twitch-bot can only receive the empty observation,

- \(I = \{\emptyset\}\); twitch-bot has only the empty state,

- \(A = \{\text{twitch}, \emptyset\}\); twitch-bot has only two actions, twitching and not twitching,

- \(\text{observe}\) always gives \(\emptyset\),

- \(\text{orient}\) always gives \(\emptyset\),

- \(\text{execute}\) describes how twitching affects the world,

Additionally, let our agent’s utility function be \(U_{\{A\}}(\text{twitch}, 0) = 1\), with \(U_{\{A\}}(a, t) = 0\) otherwise.

The optimal \(\text{decide}\) for this CWM+U always outputs \(\text{twitch}\).

Example: Akrasia

Humans sometimes suffer from akrasia, or weakness of will. These humans maximize expected utility in some mental states but act habitually in others. Such humans have utility functions of type \(\{E, I, A\}\); in some internal states, the human is an environment-based consequential agent, and in other internal states, the human is an action-based consequential agent.

Relation to Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes

We desire to compare the expressiveness of CWMs to POMDPs. Since we want to compare CWMs to POMDPs directly, we require that the agents inside each have the same types. We will call a POMDP \(P\) equivalent to CWM \(C\) if there exists a utility function \(U\) such that the agent optimal in \(P\) is optimal with respect to \(U\) in \(C\) and vice-versa.

Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes \(\subseteq\) Cartesian World Models

Given a POMDP, we can construct a Cartesian world model + utility function (CWM+U) that has an equivalent optimal consequential agent. Let \((S', A', T', R', \Omega', O', \gamma)\) be a POMDP, where

- \(S'\) is a set of states,

- \(A'\) is a set of actions,

- \(T'\) is a set of conditional transition probabilities between states,

- \(R':S' \times A' \to \mathbb R\) is the reward function,

- \(\Omega'\) is the set of observations,

- \(O'\) is the set of conditional observation probabilities, and

- \(\gamma \in [0, 1]\) is the discount factor.

Recall that an optimal POMDP agent maximizes \(\mathbb E[\sum_{t = 0}^\infty \gamma^t r_t]\), where \(r_t\) is the reward earned at time \(t\).

Let our Cartesian world model be a 7-tuple \((E, O, I, A, \text{observe}, \text{orient}, \text{execute})\) defined as follows:

- \(E = S'\),

- \(O = \Omega'\),

- \(I = \Delta S'\), the set of belief distributions over \(S'\),

- \(A = A'\),

- \(\text{observe} = O\),

- \(\text{orient}(o, i)\) describes the Bayesian update of a belief distribution when a new observation is made, and

- \(\text{execute} = T'\).

Additionally, let our agent’s utility function be \(U_{\{E, A\}}(e, a, t) = R'(e, a)\gamma^t\).

Since a POMDP has the Markov property for beliefs over states, an agent in the CWM+U has information as an agent in the POMDP. Consequential agents in CWMs maximize \(\mathbb E [ \sum_{t = 0}^\infty U_T(c_t\vert_T, t)]\). Substituting, this is equivalent to \(\mathbb E [ \sum_{t = 0}^\infty U_{\{E, A\}}(c_t\vert_{\{E, A\}}, t)]\). \(U_{\{E, A\}}(c_t\vert_{\{E, A\}}, t) = R'(e_t, a_t) \gamma^t = r_t \gamma^t\), so \(\mathbb E [ \sum_{t = 0}^\infty U_T(c_t\vert_T, t)] = \mathbb E[\sum_{t = 0}^\infty r_t \gamma^t]\). Thus our agents are maximizing the same quantity, so an agent is optimal with respect to the CWM+U if and only if it is optimal with respect to the POMDP.

Cartesian World Models \(\not\subseteq\) Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes

If we require the CWM agent to have the same type signature as in the POMDP, some CWMs do not have equivalent POMDPs. Agents in CWMs map internal states to actions, whereas agents in POMDPs map internal belief distributions over states into actions. Therefore, agents optimal in a POMDP have infinite internal states. Since one can construct a CWM with finite internal states, there must exist a CWM that cannot be converted to an equivalent POMDP.

This non-equivalence is basically a technicality and thus unsatisfying. A more satisfying treatment would use a less rigid definition of equivalence that allowed the CWM agent and the POMDP agent to have different types. In particular, it might be possible to construct a POMDP and a partition over belief states such that the elements of the partition can be put in correspondence with the internals states in the CWM. We leave exploration of this question to future work.

Structural Agents

Structural Decision Making

In contrast to consequential agents, structural agents have utility functions over structural types. We model structural agents as reasoning about a CWM with a modified decision procedure. In this framework, the agent is not trying to select utility-maximizing actions but instead trying to enforce utility-maximizing relations between consequential types. The agent is optimizing over the set of possible \(\text{decide}\) functions instead of the set of possible actions. Note that an agent optimizing in this way could still have utility functions of multiple types in the same way that an environment-based consequential agent still optimizes over its possible actions.

Let a Cartesian World Model plus Self (CWM+S) be a 8-tuple \((E, O, I, A, \text{observe}, \text{orient}, \text{execute}, \text{decide})\), where the first 7 are a CWM and the last entry is the \(\text{decide}\) function of an agent. Let \(\mathcal{CWM+S}\) be the set of all CWS+Ss.7 The utility function of a structural agent is a function \(U: \mathcal{CWM+S} \to \mathbb R\) that assigns utility to each CWS+S.

Let \(\mathcal C\) be a CWM and \(\text{decide}:I \to A\) be a decision function. Let \(\mathcal C + \text{decide}\) be the CWM+S that agrees with \(\mathcal C\) for the first 7 entries and is equal to \(\text{decide}\) for the 8th. This construction omits acausal implications of changing \(\text{decide}\). A method of constructing CWM+Ss that include acausal implications is currently an open problem.

Recall that \(A^I\) is the set of all functions from \(I\) to \(A\). A structural agent reasoning according to a CWM \(\mathcal C\) acts to implement \(\text{decide}^* = \text{arg}\max_{\text{decide} \in A^I} U(\mathcal C + \text{decide})\). Behaviorally, when given an internal state \(i\), an optimal structural agent will take \(a = \text{decide}^*(i)\)

Examples

Pseudo-example: Updateless Decision Theory

An agent using updateless decision theory (UDT) is a structural agent with a consequential utility function over environmental states reasoning over a CWM+S that includes acausal implications. In order to convert the consequential utility function \(U_b\) into a structural one \(U_s\), we simply define \(U_s(\mathcal C + \text{decide})\) by rolling out \(\mathcal C + \text{decide}\) to produce a sequence \(e_0, e_1, e_2, ...\) of environmental states and let \(U_s(\mathcal C + \text{decide}) = \sum_{t = 0}^\infty U_b(e_t)\lambda^t\) with some discount factor \(\lambda\).

Example: Structural HCH-bot

In the limit of training, imitative amplification produces Human consulting HCH(HCH). We describe a structural agent that is implementing HCH.8 The agent receives input via computer terminal and outputs text to the same terminal. It has 1 Mb of memory. In the following, let \(\Sigma\) be the alphabet of some human language, including punctuation and spaces:

- \(E\) is all ways the universe could be,

- \(O = \Sigma^*\), all finite strings from \(\Sigma\),

- \(I = \mathcal P(\{n \vert 0 \leq n < 8 \times 10^6\})\), the set ways 1 Mb of memory can be,

- \(A = \Delta \Sigma^{<1000}\), the set of probability distributions over strings from \(\Sigma\) of less than 1000 characters,

- \(\text{observe}\) yields the command typed in at the computer terminal with probability ~1,

- \(\text{orient}\) stores the last 1 Mb of the string given by \(\text{observe}\),

- \(\text{execute}\) describes the world state after outputting a given string at the terminal.

Let \(P\) be some distribution over possible inputs. Let \(\text{HCH}: I \to \Delta A\) be the HCH function. Let our agents utility function \(U\) be defined as \(U(\text{decide}) = \mathbb E_{i \sim P}[KL(\text{HCH}(i) \vert\vert \text{decide}(i))]\).9

It is unclear which \(P\) makes the agent behave properly. One possibility is to have \(P\) be the distribution of what questions a human is likely to ask.10 Any powerful agent likely has a human model, so using the human distribution might not add much complexity.

Example: Structural Decoupling

A consequential approval-maximizing agent takes the action that gets the highest approval from a human overseer. Such agents have an incentive to tamper with their reward channels, e.g., by persuading the human they are conscious and deserve reward.

In contrast, a structural approval-maximizing agent implements the \(\text{decide}\) function that gets the highest approval from a human overseer. Such agents have no incentive to directly tamper with their reward channels, but they still might implement decision functions that appear safe without being safe. However, a \(\text{decide}\) function that overtly manipulates the overseer will get low approval, so structural approval-maximizing agents avoid parts of the reward tampering problem.

This example is inspired by the decoupled approval described in Uesato et al.11

Types of Structural Agents

There are roughly four types of consequential agents, one for each consequential type. This correspondence suggests there are four types of structural agents, one for each structural type.

Agents with utility functions over \(\text{decide}\) are coherent. However, since we do not include acausal implications when constructing a CWM+S, agents with utility functions over \(\text{orient}\), \(\text{observe}\), or \(\text{execute}\) have constant utility. More specifically, the agent only has control over its own \(\text{decide}\) function, which does not have influence over \(\text{orient}\), \(\text{observe}\), or \(\text{execute}\) (within the CWM+S), so agents with utility functions over those types will not be able to change anything they care about. How structural agents act when we include acausal implications is currently an open problem.

Utility/Decision Distinction

Besides having utility functions with different type signatures, structural agents also make decisions differently. We have two dimensions of variation: structural versus consequential utility functions and structural versus consequential decision-making. These dimensions produce four possible agents: pure consequential, pure structural, decision-consequential utility-structural, and decision-structural utility-consequential.

A pure consequential agent makes consequential decisions to maximize a consequential utility function; it reasons about how taking a certain action affects the future sequence of consequential types. A purely consequential environment-based agent takes actions to maximize \(\sum_{t = 0}^\infty U(e_t) \gamma ^t\) for some discount factor \(\gamma\).

A pure structural agent makes structural decision to maximize structural utility function; it reasons about how implementing a certain \(\text{decide}\) affect the structural types of its CWM+S. A purely structural \(\text{decide}\)-based agent implements the \(\text{decide}\) function to maximize \(U(\mathcal C + \text{decide})\), where \(\mathcal C\) is the agent’s CWM.

A decision-consequential utility-structural agent makes consequential decisions to maximize a structural utility function; it reasons about how taking a certain action affects how it models the world. For example, a decision-consequential utility-structural \(\text{orient}\)-based agent might rewrite its source code. If decision-consequential utility-structural agents are not time-limited myopic, they will take over the world to securely achieve desired CWM structural properties.12

A decision-structural utility-consequential agent makes structural decisions to maximize a consequential utility function. If only causal implications are included, a decision-structural utility-consequential agent behaves identically to a purely consequential agent. If we include acausal implications, decision-structural utility-consequential agents resemble UDT agents. Traditional UDT agents are decision-structural utility-consequential environment-based agents.

Pure Structural \(\text{decide}\)-based Agents = Time-Limited Myopic Action/Internal-based Behavioral Agents

Pure structural \(\text{decide}\)-based agents can be expressed as time-limited myopic action/internal-based consequential agents and vice versa. Let \(\text{decide}^*\) be optimal according to our pure structural agent’s utility function. To construct an action/internal-based consequential utility function for which \(\text{decide}^*\) is optimal, define \(U\) such that \(\forall i \in I, a \in A: U(i, a) = 1 \iff \text{decide}^*(i) = a\) and \(0\) otherwise. To show the inverse, construct a structural utility function maximal utility to the time-limited myopic action/internal-based consequential agent’s decision function.

These agents are behaviorally identical but mechanistically distinct; they use different decision mechanisms and have different types of utility functions.

Connection to Act-Based Agents

Act-based agents focus on satisfying users’ short-term instrumental preferences. These agents might be safe insofar as learning short-term preferences naturally avoids catastrophic generalization. For instance, learning that killing is bad might be easy, allowing weak agents to avoid catastrophe.

Paul Christiano postulates a gradient of agents that satisfy “narrow” preferences to “broad” preferences:

Consider a machine choosing a move in a game of chess. I could articulate preferences over that move (castling looks best to me), over its consequences (I don’t want to lose the bishop), over the outcome of the game (I want to win), over immediate consequences of that outcome (I want people to respect my research team), over distant consequences (I want to live a fulfilling life).

In contrast, our framework makes a sharp distinction between agents that use consequential versus structural decision-making. The above spectrum is composed of consequential agents with differing amounts of time-limited myopia. Such agents are unsafe because they would take over the world if they could do so fast enough. In general, all agents that reason over their actions’ consequences are dangerous because we do not know reality’s causal structure. We hope that structural agents provide a step towards constructing agents that do not use intrinsically dangerous decision-making procedures.

Input Distribution Problem

\(\text{decide}\)-based structural agents attempt to implement specific \(\text{decide}\) functions, which will often require determining the distance to a target function, e.g. the HCH function. Unless the distance metric treats all inputs identically, such as with sup norm, the metric requires a distribution over inputs. For instance, recall structural HCH-bots’s utility function, \(U(\text{decide}) = \mathbb E_{i \sim P}[KL(\text{HCH}(i) \vert\vert \text{decide}(i))]\), depends on an input distribution \(P\).

However, the distribution of inputs depends on how the agent responds to various inputs, creating an acausal implication between the agent’s actions and what inputs it receives. For example, what you google depends on Google’s capabilities. Since the agent’s utility depends on the inputs it receives, this acausal implication incentivizes the agent to implement a \(\text{decide}\) function that shifts the distribution towards high-scoring inputs. The agent is not optimizing over \(\text{decide}\) functions, but rather jointly optimizing over \(\text{decide}\), input distribution pairs. More concretely, the agent has an incentive to hide its full capabilities so it will not be asked difficult questions. If the agent can only answer questions with obvious answers, it will probably be asked questions with easy answers, acausally shifting \(P\) to a higher utility distribution.13

This acausal implication reduces capabilities, but it also might be a problem for alignment. The capabilities hit from acausally optimizing the input distribution does not appear to intrinsically produce alignment failures, but the problem arises only when the agent thinks of itself as having logical control over other instances of itself. This pattern of reasoning potentially results in deceptive alignment arising through acausal means. 14 In general, any agent that has uncertainty over its input might be able to acausally influence the input distribution, potentially resulting in undesirable behavior.

Conditional Agents

Conditional Decision Making

Traditional utility functions map types, e.g., environmental states, to utility. In contrast, conditional utility functions map types to utility functions. For example, an environment-conditional utility function takes in an environmental state and yields a utility function over other environmental states, actions, observations, internal states, etc. We will refer to the utility function given by a conditional utility function as the base utility function.

Conditional agents might make decisions in the following way. Let \(\mathcal U\) be a conditional utility function. Upon having internal state \(i\), the agent acts as if it has utility function \(U = \mathcal U(\text{argmax}_{s \in \mathcal S}P(s \vert i))\), where \(\mathcal S\) varies between \(\mathcal E\), \(\mathcal O\), \(\mathcal I\), and \(\mathcal A\) depending on whether \(\mathcal U\) is environmental, observational, or structural conditional. The agent reasons as if it were a structural or consequential agent depending on the utility function.15Action-based agents might run into issues around logical uncertainty.

Examples

Example: Value Learner

A simple value-learning agent observes a human and infers the human utility function, which the agent then optimizes. Ignoring the issues inherent in inference, such an agent can be thought of as having a conditional utility function that maps observations to utility functions over environmental states, i.e., of type \(\mathcal O \to (\mathcal E \times \mathbb N \to \mathbb R)\) (Recall that we include explicit time-dependence to allow for arbitrary discounting possibilities).

Shah et al.’s Preferences Implicit in the State of the World attempts to construct agents that infer human preferences based on the current environmental state. In our framework, these agents have conditional utility functions that map environmental states to utility functions over environmental states, i.e., of type \(\mathcal E \to (\mathcal E \times \mathbb N \to \mathbb R)\).

Example: Argmax

Given a CWM, \(\text{argmax}\) takes in a utility function and outputs the action that maximizes that utility function. Since \(\text{argmax}\) only has access to its internal representation of the utility function, we can think of \(\text{argmax}\) as having a conditional utility function that maps internal states to utility functions over all types, i.e. of type \(\mathcal I \to (\mathcal A \times \mathcal O \times \mathcal E \times \mathcal I \times \mathbb N \to \mathbb R)\).

Example: Imprinting-bot

Imprinting-bot is an agent that tries to imitate the first thing it sees, similar to how a baby duck might follow around the first thing it sees when it opens its eyes. Such an agent can be thought of as having a conditional utility function that maps observations to utility functions over \(\text{decide}\) functions, i.e., of type \(\mathcal O \to (\mathcal A^{\mathcal I} \to \mathbb R)\).

Example: Conditional HCH-bot

Recall that \(\text{HCH}: \mathcal I \to \Delta \mathcal A\) is the HCH function. Let \(\text{HCH}(i)\) be the distribution of actions HCH would take given internal state \(i\). Let \(\text{HCH}(i)(a)\) be the probability that HCH takes action \(a\) when internal state \(i\).

Structural HCH-bot gets higher utility for implementing \(\text{decide}\) functions that are closer to HCH in terms of expected KL-divergence relative to some input distribution. Conditional behavioral-HCH-bot conditions on the internal state, then gets utility for outputting distributions closer to the distribution HCH would output given its current internal state as input. More precisely, conditional behavioral-HCH-bot has a conditional utility function defined by \(\mathcal U:\mathcal I \to (\mathcal A \times \mathbb N \to \mathbb R) := i \mapsto ((a, n) \mapsto -\log(\text{HCH}(i)(a)) \text{ if } n = 0 \text{ else } 0)\).

Conditional structural-HCH-bot conditions on the internal state, then attempts to implement a \(\text{decide}\) function close to HCH. More precisely, conditional structural-HCH-bot has a conditional utility function described by \(\mathcal U: \mathcal I \to (\mathcal A^\mathcal I \to \mathbb R) := i \mapsto (\text{decide} \mapsto KL(\text{HCH}(i)\vert\vert\text{decide}(i)))\).

Conditioning Type is Observationally Indistinguishable

Following a similar argument to previous sections, the type an agent conditions upon cannot be uniquely distinguished observationally. To see this, note that the only information a conditional agent has access to is the internal state, so it must back-infer observation/environmental states. Thus, internal-conditional utility functions can be constructed that mimic conditional utility functions of any conditioning type. Since back-inference might be many-to-one, the reverse construction is not always feasible.

However, there seem to be natural ways to describe certain conditional agents. For instance, one can consider a value learning agent that conditions upon various types. An environmental-conditional value learner looks at the world and infers a utility function. An observational-conditional value learner needs to observe a representation of the utility function. An internal-conditional value learner needs a representation of the utility function in its internal state. At each stage, more of the information must be explicitly encoded for “learning” to take place.

These agents can be distinguished by counterfactually different \(\text{observe}\) and \(\text{orient}\) maps. Back inference should happen differently for different \(\text{observe}\) and \(\text{orient}\) mappings, causing agents to potentially act differently. Environmental-conditional agents have different utility functions (and potentially take different actions) if either the \(\text{observe}\) or \(\text{orient}\) mappings differed. Observation conditional agents are stable under changes to \(\text{observe}\), but act differently if \(\text{orient}\) differed. Internal conditional agents should not care if either \(\text{observe}\) or \(\text{orient}\) differed.

Doing back inference at any point opens the door to the input distribution problem; only internal-conditional agents do not back-infer.

Structural Conditional Utility Functions

In addition to consequential conditional utility functions, there are also structural conditional utility functions. Instead of conditioning on a particular environmental state, an agent can condition upon \(\text{execute}\), e.g. by having a conditional utility function of type \(\mathcal E^{\mathcal A} \to (\mathcal E \times \mathbb N \to \mathbb R)\). Such structural conditional agents have utility functions that depend on their model of the world.

For instance, Alice might have a utility function over 3D environmental states. However, suppose that Alice found out the world has four dimensions. Alice might think she gets infinite utility. However, Alice’s utility function previously mapped 3D environmental states to utilities, so 4D states produce a type error. For Alice to get infinite utility, a 4D state’s utility must generalize to be the infinite sum of all the 3D states it’s made of. Instead, Alice might get confused and start reasoning about what utility function she should have in light of her new knowledge. In our framework, Alice has a structural-conditional utility function, i.e., she assigns utilities to 3D environmental states conditional on the fact that she lives in a 3D world.

In general, structural conditional utility functions are resistant to ontological crises – such agents will switch to different base utility functions upon finding out their ontological assumptions are violated.

Type Indistinguishability

The type of a conditional utility function is often mathematically identical to the type of a consequential utility function. For example, a conditional utility function that takes internal states and gives a utility function over actions has type \(\mathcal I \to (\mathcal A \times \mathbb N \to \mathbb R)\), which is mathematically equivalent to an internal/act consequential utility function \(\mathcal I \times \mathcal A \times \mathbb N \to \mathbb R\). This equivalence is problematic because consequential utility functions do not possess many desirable safety properties.

We currently remain confused by the implications of this problem but sketch out a potential resolution. Classical Bayesianism accepts dogmatism of perception, i.e., observations, once observed, are believed with probability one. Similarly, we might require that conditional agents accept dogmatism of conditioning, i.e., the agent must believe that the object they are conditioning on occurs with probability one. This requirement neatly solves the input distribution problem; even if the agent thought it had logical control of the input distribution, the input could not have been anything else.

Contrast this with one of Demski’s desiderata in Learning Normativity:

Learning at All Levels: Although we don’t have perfect information at any level, we do get meaningful benefit with each level we step back and say “we’re learning this level rather than keeping it fixed”, because we can provide meaningful approximate loss functions at each level, and meaningful feedback for learning at each level. Therefore, we want to be able to do learning at each level.

Demski’s motivation is that any given level might be corruptible, so learning should be able to happen on all of them. Our motivation is that if an input can be influenced, then it will, so the agent must think of it as fixed.

No Uncertainty Upstream of Utility

In general, many problematic situations seem to arise when agents have uncertainty that is logically upstream of the utility they ultimately receive.16An agent with uncertainty over the input distribution suffers from the input distribution problem.17An agent with uncertainty over how much utility its action will be power-seeking. We will call the former type of uncertainty historical uncertainty and the latter consequential uncertainty. Agents also must be uncertain about what actions they will take, which we call logical uncertainty.

We are interested in agents that possess no historical or consequential uncertainty. Such agents might be described as maximizing utility directly instead of maximizing expected utility, as there is no uncertainty over which to take an expectation.

We suspect avoiding historical uncertainty is the only way to avoid the input distribution problem described above because if agents have uncertainty logically upstream of utility they eventually receive, then they have an incentive to acausally influence the distribution to get more utility. We also suspect that avoiding consequential uncertainty is a way to eliminate power-seeking behavior and undesirable outcomes like edge instantiation.

The trick employed in Conditional Decision Making is to collapse the input distribution into the maximum probability instance. Thus an environmental-conditional agent will optimize the most probable base utility function instead of optimizing the weighted mixture represented by the probability distribution. This does not entirely avoid the input distribution problem, as the agent still has logical influence over what the maximum probability back-inference is, but it reduces the amount of logical control an agent has.

In practice, the agent will have logical control over parts of the input distribution. It remains an open question as to how to get an agent to think they do not have logical control.

Problem: Empirical Uncertainty

Agents with no historical or consequential uncertainty will still have uncertainty over parts of their world model. For instance, conditional HCH-bot will have uncertainty over its model of a human, which will translate into uncertainty as to what HCH would output for any given input. Since conditional HCH-bot’s utility depends on how well it can approximate HCH, this means that there must be uncertainty that is logically upstream of the utility the agent receives. One might hope that the agent does not think of itself as having logical control over the human input-output mapping.

Drawing a natural boundary between these two types of uncertainty remains an open problem.

Problems

Cartesian boundaries are not real

One major problem with this way of conceptualizing agency is that Cartesian boundaries are part of the map, not the territory. In reality, there is no distinction between agent and environment. What happens when an agent discovers this fact is relatively unclear, although we think it will not cause capabilities to disintegrate.

Humans have historically thought they were different from the environment. When humans discovered they were made of atoms, they were still able to act. Anthropomorphizing, humans have empirically been robust to ontological crises, so AIs might also be robust.

Even if structural agents can continue acting upon discovering the Cartesian boundary is not real, there might be other undesirable effects. If the agent begins conceptualizing itself as the entire universe, a utility function over \(\text{decide}\) reduces to a utility function over environmental states; desirable properties of structural agents are lost. As another example, the agent could start conceptualizing “become a different type of agent” as an action, which might cause it to self-modify into an agent that lacks desirable properties.

In general, the way a structural agent models the CWM boundary might change the action set and the internal state set. Depending on how the agent’s utility function generalizes, this might cause undesirable behavior.

Myopia might be needed

Purely consequential act/internal-based farsighted agents are incorrigible. If an approval-maximizing agent picks the action trajectory that maximizes total approval, it will avoid being shut down to gain high approval later. While structural agents avoid some of these problems, the highest utility \(\text{decide}\) function needs to be myopic, else the problem reappears. The base utility function output by a conditional utility function must also be myopia, else the agent will act to preserve its utility function across time.

This analysis suggests myopia might be necessary for safe agents, where myopic agents “only care about the current episode” and “will never sacrifice reward now for reward later.” Currently, myopia is not understood well enough to know whether it is sufficient. Myopia also has a number of open problems.

Training for types

If there are agents that possess desirable safety properties, how can we train them? The obvious way is to reward them for having that type. However, knowing an agent is optimal according to some reward function does not constrain the type of the agent’s utility function. For instance, rewarding an agent for implementing a decision function that takes high approval actions is indistinguishable from rewarding the agent for creating environments in which its actions garner high approval.

Many agents are optimal for any reward, so the resulting agent’s type will depend on the training process’s inductive biases. In particular, we expect the inductive bias of stochastic gradient descent (SGD) to be a large contributing factor in the resulting agent.18 We are eager for exploration into how the inductive biases of SGD interact with structural agents.

Given that behavior does not determine agent type, one could use a training process with mechanistic incentives. For instance, instead of rewarding the agent for taking actions, one can also reward the agent for valuing actions. We could also reward agents for reasoning over decision functions instead of actions or lacking uncertainty of certain types. This training strategy would require advances in transparency tools and a better mechanistic understanding of structural agents.[^current work]

Conclusion

If one supposes a Cartesian boundary between agent and environment, the agent can value four consequential types (actions, environments, internals, and observations) and four structural types (\(\text{observe}\), \(\text{orient}\), \(\text{decide}\), and \(\text{execute}\)). We presented Cartesian world models (CWMs) to formally model such a boundary and briefly explored the technical and philosophical implications. We then introduced agents that explicitly maximize utility functions over consequential and structural properties of CWMs.

We compared consequential agents, structural agents, and conditional agents and argued that conditional agents avoid problems with consequential and structural agents. We concluded by presenting multiple problems, which double as potential directions for further research.

Appendix

These sections did not fit into the above structure.

The Two Wireheaders

Two types of consequential agents are “wireheading”: internal-based and observation-based agents. Internal-based agents wirehead by changing their internal states, e.g., by putting wires in their brain. Observation-based agents wirehead by changing their observations, e.g., by constructing a virtual reality. Internal state-based agents also wirehead by changing their observations, but observation-based agents will not change their internal states (typically).

These two agents demonstrate “wireheading” does not carve reality at its joints. In reality, internal and observation-based agents are maximizing non-environment-based utility functions. Internal-based or observation-based agents might look at environment-based agents in confusion, asking, “why don’t they just put wires in their head?” or “have they not heard of virtual reality?”

Consider: are action-based agents wireheading? Neither yes nor no seems reasonable, which hints that wireheading is a confused concept.

Types are Observationally Indistinguishable

In most cases, it is impossible to determine an agent’s type by observing its behavior. In degenerate cases, any set of actions is compatible with a utility function of any combination of \(\{E, I, A, O\}\).19 However, by employing appropriate simplicity priors, we guess the agent’s approximate type.

As an analogy, all nondeterministic finite automaton (NFA) can be translated into deterministic finite automaton (DFA). What does it mean to say that a machine “is an NFA”? There is an equivalent DFA, so “NFA” is not a feature of the machine’s input-output mapping, i.e., “being an NFA” is not a behavioral property.

Converting most NFA into DFA requires an exponential increase in the state-space. We call a machine an NFA if describing it as an NFA is simpler than describing it as a DFA. Similarly, we might call an agent “environment-based” if describing its behavior as maximizing an environment-based utility function is simpler than describing it as maximizing a non-environment-based utility function.

Unlike NFAs and DFAs, however, one can construct degenerate CWMs that rule out specific type signatures. Suppose that the environment consisted only of a single switch, and the agent could toggle the switch or do nothing. If an optimal agent always toggled the switch, we could infer that the agent was not purely environment-based.20

In general, the VNM Theorem rules out some types of utility functions for some sequences of actions. If the agent can act to leave itself unchanged, loops of the same sequences of internal states rule out utility functions of type \(\{I\}\). Similarly, loops of the same (internal state, action) pairs rule out utility functions of type \(\{I\}, \{A\}\) and \(\{I, A\}\). Finally, if the agent ever takes different actions, we can rule out a utility function of type \(\{A\}\) (assuming the action space is not changing).5

However, to see that agent types cannot be typically distinguished behaviorally, note that an agent can always be expressed as a list of actions they would take given various observations and internal states. Given reasonable assumptions, one can construct utility functions of many types that yield the same list.21 This flaw with behavioral descriptions justifies our intention that the CWM+U framework captures how the agent models its interactions with the world - a mechanistic property, not a behavioral one.

Example: human

Alice has a utility function over the environment. Alice’s only way to obtain information is by observation, so we can construct a utility function over observations that results in indistinguishable behavior. Alice refuses to enter perfect VR simulations, so we suppose that Alice intensely disvalues the observation of entering the simulation. Observation-based Alice is more complicated than environment-based Alice but is compatible with observed behavior.

Observations are distinguishable only when they produce different internal states, so we can construct a utility function over internal states that results in indistinguishable behavior. Alice does not take drugs to directly alter the internal state, so we suppose they intensely disvalue the internal state of having decided to take drugs. Internal-based Alice is more complicated than environment-based Alice but is compatible with observed behavior.

Alice takes different actions, so we can rule out a pure action-based utility function. Since internal states are only distinguishable by what actions they cause Alice to take, we can construct an internal/action-based utility function that results in indistinguishable behavior. Alice is willing to sacrifice their life for a loved one, so we suppose they get immense utility from taking the action of saving their loved one’s life when they believe said loved one is in danger. Internal/action-based Alice is more complicated than environment-based Alice but is compatible with observed behavior.

Natural descriptions

In the above, there seemed to be a “natural” description of Alice.22 Describing Alice’s behavior as maximizing an environment-based utility function did not require fine-tuning, whereas an observation-based utility function had specific observations rate very negatively. We can similarly imagine agents whose “natural” descriptions use utility functions of other type signatures, the trivial examples being agents who model themselves in a CWM and maximize a utility function of that type.

It is essential to distinguish between a mechanistic and a behavioral understanding of CWMs. Under the mechanistic understanding, we consider agents that explicitly maximize utility over a CWM, i.e., the agent has an internal representation of the CWM, and we need to look inside the agent to gain understanding. Under the behavioral understanding, we are taking the intentional stance and asking, “if the agent internally modeled itself as being in a CWM, what is the simplest utility function it could have that explains its behavior?”

Attempting to understand agents behaviorally using CWMs will sometimes fail. For instance, a thermostat is a simple agent. One might describe it as an environment-based agent whose goal is to maintain the same temperature. However, the thermostat only cares about the temperature in a tiny region around its sensors. We could describe it as an observation-based agent that wants to observe a specific temperature. Nevertheless, there is a 1-1 correspondence between observations and internal states, so it seems equally accurate to describe the thermostat as internal-based. Finally, we can describe it as an internal/action-based agent that wants to increase the temperature when it is low but decrease it when it is high.

We strain to describe a thermostat as environment-based or internal/action-based. However, there is a 1-1 correspondence between observation and internal state, so it is equally simple to describe the thermostat as observation-based or internal-based.

It can also be unclear what type of utility function suboptimal agents have. Suppose an agent does not know they can fool their sensors. In that case, an observation-based agent will act the same as an environment-based agent, making it impossible to obtain a mechanistic understanding of the agent by observing behavior.

“Becoming Smarter”

What exactly does it mean for an agent to improve? Our four-map model allows us to identify four potential ways. In what follows, we assume the agent is farsighted. We also implicitly relax other optimality assumptions.

- \(\text{observe}\): An agent could expand \(O\) or reduce the expected entropy of \(\text{observe}(e, a)\). For example, an agent could upgrade its camera, clean the camera lens, or acquire a periscope. Many humans employ sensory aids, like glasses or binoculars.

- \(\text{orient}\): An agent could both expand \(I\) and reduce the expected entropy of \(\text{orient}(o, i)\). For example, an agent could acquire more memory or better train its feature detection algorithms. Many humans improve their introspection ability and memories by meditating or using spaced repetition software.

- \(\text{decide}\): An agent could implement a \(\text{decide}\) function that better maximizes expected future utility. For example, a chess-playing agent could search over larger game trees. Many humans attempt to combat cognitive biases in decision-making.

- \(\text{execute}\): An agent could expand \(A\) or decrease the expected entropy of \(\text{execute}(e, a)\). For example, a robot could learn how to jump, build itself an extra arm, or refine its physics model. Many humans practice new skills or employ prostheses.

Many actions can make agents more powerful along multiple axes. For example, increasing computation ability might create new actions, increase decision-making ability, and better interpretation processing. Moving to a different location can both create new actions and increase observation ability.

-

This drawing is originally from Embedded Agents ↩

-

The decision-making model known as the OODA Loop inspired this naming scheme. Acting has been renamed to executing to avoid confusion with act-based agents. ↩

-

See Conditions for Mesa-Optimization for further discussion. ↩

-

See Locality of Goals for a related discussion. ↩

-

Technically, there could be two actions that both had maximal utility. This occurrence has measure 0, so we will assume it does not happen. ↩ ↩2

-

Hadfield-Menell, Dylan, Smitha Milli, Pieter Abbeel, Stuart Russell, and Anca Dragan. “Inverse Reward Design.” ArXiv:1711.02827 [Cs], October 7, 2020. http://arxiv.org/abs/1711.02827. ↩

-

Constructing this set is technically impossible. In practice, it can be replaced by the set of all finite CWS+Ss. ↩

-

We contrast this to an agent whose internals are structured like HCH, i.e., it has models of humans consulting other models of humans. An agent with this structure is likely more transparent and less competitive than an agent trying to enforce the same input-output mapping as HCH. ↩

-

This utility function is flawed because the asymmetry of KL-divergence might make slightly suboptimal agents catastrophic, i.e., agents that rarely take actions \(\text{HCH}\) would never take will only be slightly penalized. Constructing a utility function that is not catastrophic if approximated remains an open problem. ↩

-

What a human asks the agent depends on the agent’s properties, so using the human distribution has acausal implications. See Open Problems with Myopia for further discussion. ↩

-

Uesato, Jonathan, Ramana Kumar, Victoria Krakovna, Tom Everitt, Richard Ngo, and Shane Legg. “Avoiding Tampering Incentives in Deep RL via Decoupled Approval.” ArXiv:2011.08827 [Cs], November 17, 2020. http://arxiv.org/abs/2011.08827. ↩

-

The inverse might not hold. Time-limited myopic agents might also take over the world for reasons described here ↩

-

These concerns are similar to the ones illustrated in Demski’s Parable of Predict-O-Matic. ↩

-

See Open Problems with Myopia for further discussion. ↩

-

Here, the agent is reasoning according to the maximum probability world state, a trick inspired by Cohen et al.’s Asymtotically Unambitious Artificial General Intelligence. ↩

-

What we mean by “upstream” is unclear but is related to the concept of subjunctive dependence from Functional Decision Theory: A New Theory of Instrumental Rationality. ↩

-

If an agent’s experiences shape who they are, uncertainty over the input distribution might be viewed as a special case of anthropic uncertainty. ↩

-

See Understanding Deep Double Descent for more discussion. ↩

-

This is related to Richard’s point that coherent behavior in the world is an incoherent concept. ↩

-

Technically, both environmental states could have equal utility, making all policies optimal. This occurrence has measure 0, so we will assume it does not happen. ↩

-

I am not sure what assumptions are needed, but having no loops of any type and the agents always taking the same action in the same (environmental state, internal state) pair might be sufficient. ↩

-

Here, we roughly mean “there is probably some notion of the complexity of an agent’s description that has some descriptions as simpler than others, even though we do not know what this notion is yet.” ↩